Month: November 2012

God Bless our veterans! 11-11-12…. WWII vets are nearly all gone….Korean War vets are vanishing….Vietnam vets get Zero respect…..Heaven help us….

Sleeper, turbo bike……..

Norton Trail Bike…

Brough and Vincent, the best of the best……

Vacuum Crevise Tool for exhaust tips…Burgess Muffler?

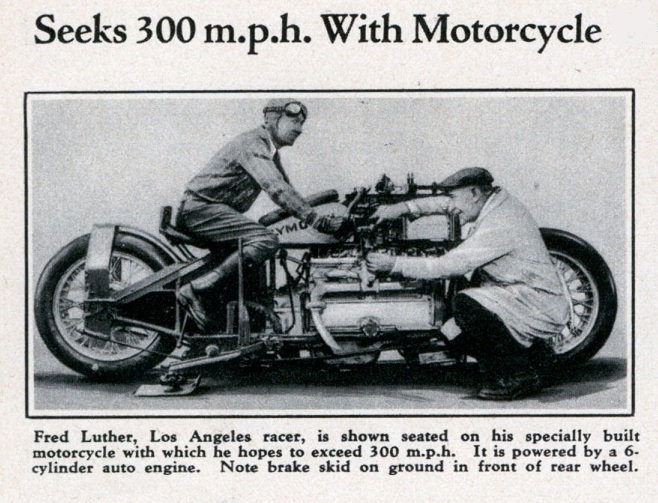

“Fred Luther was an employee of Chrysler and he prevailed upon the company to supply him with motive power in his challenge to become this man. Chrysler responded by supplying Luther with a complete 1934 PF six cylinder engine and transmission. Already an experienced motorcycie racer, Luther began the necessary modifications to a ‘cycle to accomodate its new power plant.

“Fred Luther was an employee of Chrysler and he prevailed upon the company to supply him with motive power in his challenge to become this man. Chrysler responded by supplying Luther with a complete 1934 PF six cylinder engine and transmission. Already an experienced motorcycie racer, Luther began the necessary modifications to a ‘cycle to accomodate its new power plant.

The basic bike was built around a much modified Henderson “X” cycle. First the engine was mounted lengthwise in the chassis, after the frame had been lengthened and strengthened as necessary. The steering was mounted far back on the frame, behind the center point of the engine, with heavy roller chain implemented to reach a lack shaft on the front fork. Skid plates were mounted on either side, with a dual purpose in mind. They managed to keep the bike in an upright position as well as acted as brakes on the surface of the salt to slow the bike down. Firestone supplied a set of 8 ply tires in a 30×5″ size, with a tread less design for use on the salt.

Big dream for a Plymouth……..

The engine itself was sent to the speed shops of California’s Harry Miller, (a name all too familiar to losers at Indy’s famed brickyard, with Miller’s creations taking the checkered flag for years on end). Normally rated at 77 horsepower at 3,600 rpm, the six came out snorting 125 horses at 4,500 rpm. Upon completion the “bike” weighed 1,500 pounds and ran a tape to nearly 11 feet long. The rider sat just in front of the rear tire and lay flat on his belly over the top bar of the frame.

The bike was built over the winter of 1934-35 and made its appearance on the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1935. There, under the watchful eye of the official timers, Fred Luther set out on his way to fame, glory and hopefully, $10,000 in prize money. The rules at Bonneville were the same then as they are today. To qualify for a record you must run the course both directions–down the course and then back again. The average speed of both runs determines whether or not the record has been set.

Laying into the wind, Luther pushed the bike on the first leg of the record attempt and got the bike up to aspeed of 140 miles per hour. On the return run, feeling more confident, Luther continued to “open up” the engine until trouble struck–he broke a connecting rod at about 180 miles per hour–the bike was still in second gear!

Bringing the bike to a coasting halt Luther decided he had enough of the record attempt and never again attempted to reach the 300 mile per hour mark on the bike although he always did feel that the Plymouth Henderson X-Miller combination could reach that lofty flgure–if only someone were willing to ride it that fast..”